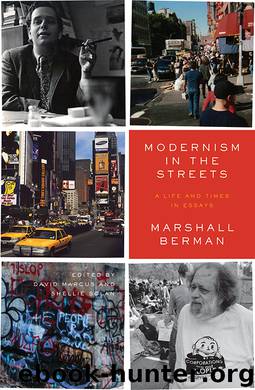

Modernism in the Streets by Marshall Berman

Author:Marshall Berman

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Verso Books

And yet, within a few days of this essay, Lukács had decided to make the leap. What changed his mind? It’s hard to say for sure. “Tactics and Ethics” offers a pragmatic argument that in East Central Europe in 1919, the likely political alternatives are either a communist revolution or a fascist dictatorship; at this time, in this place, liberal democracy is simply not in the cards. This argument is plausible but has a limited force. It justifies participating in a communist movement on the grounds that it is the lesser of two available evils. But Lukács invests far more emotion in communism, and expects far more from it, than his pragmatic argumentation could ever comprehend. We need to look between the lines of his text and search out the emotional subtext. The most intense emotion in the inner world of “Tactics and Ethics” is Lukács’s sense of guilt. The ethical rhetoric he speaks in at first sounds Kantian; we should act as if we were universal legislators, ethically responsible for the whole world. But if we listen for the feeling, it is less Kant than Dostoevsky, or Kant as he might have been remembered by Raskolnikov.8

Thus, for Lukács, we really are responsible for all the oppression, violence, and murder in the world. If we become communists, we are guilty of all the murders committed in the name of communism, not only now but in the indefinite future, “just as if we had killed them all” (my emphasis). If we refuse to commit ourselves to communism, and fascism triumphs instead, we are guilty of all fascist murders, now and to come. No matter what happens, whatever we do or don’t do, we are all murderers, there is no way to escape the blood on our hands. What can a murderer do? Is there any way to atone? These were the sorts of questions that were tormenting Lukács at the end of 1918. He seems to have concluded that if the criminal were to lean to the left, his crimes might actually accomplish something, his murders might help to end (or at least diminish) murders, his lies might open the way to some sort of truth.

In his later years, Lukács disparaged the thinking that led to his conversion as “utopian,” “messianic,” “sectarian.” It wasn’t till later on, he said, that he became a “realist” and “materialist” and learned true Marxism. After digging deep into his early work, I would argue the exact opposite: that at the high tide of his messianic hopes, Lukács’s moral and political thinking was clear, honest, and deeply attuned to material realities, in the finest Marxist tradition. He said repeatedly, in 1919, that it was impossible to know how history was going to turn out, that all political choices would have to be continually reappraised, that the ethical subject would have to weigh the violence and evil he helped to perpetrate against the actual freedom and happiness that he was helping to create.

It was only afterward, when

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18993)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12175)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8870)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6854)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6243)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5759)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5706)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5479)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5408)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5196)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5127)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5065)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4937)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4898)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4757)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4724)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4677)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4484)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4472)